This review is going to be very nerdy about American barbecue. Please consider yourself duly warned. Happy? Great. Let’s define some terms.

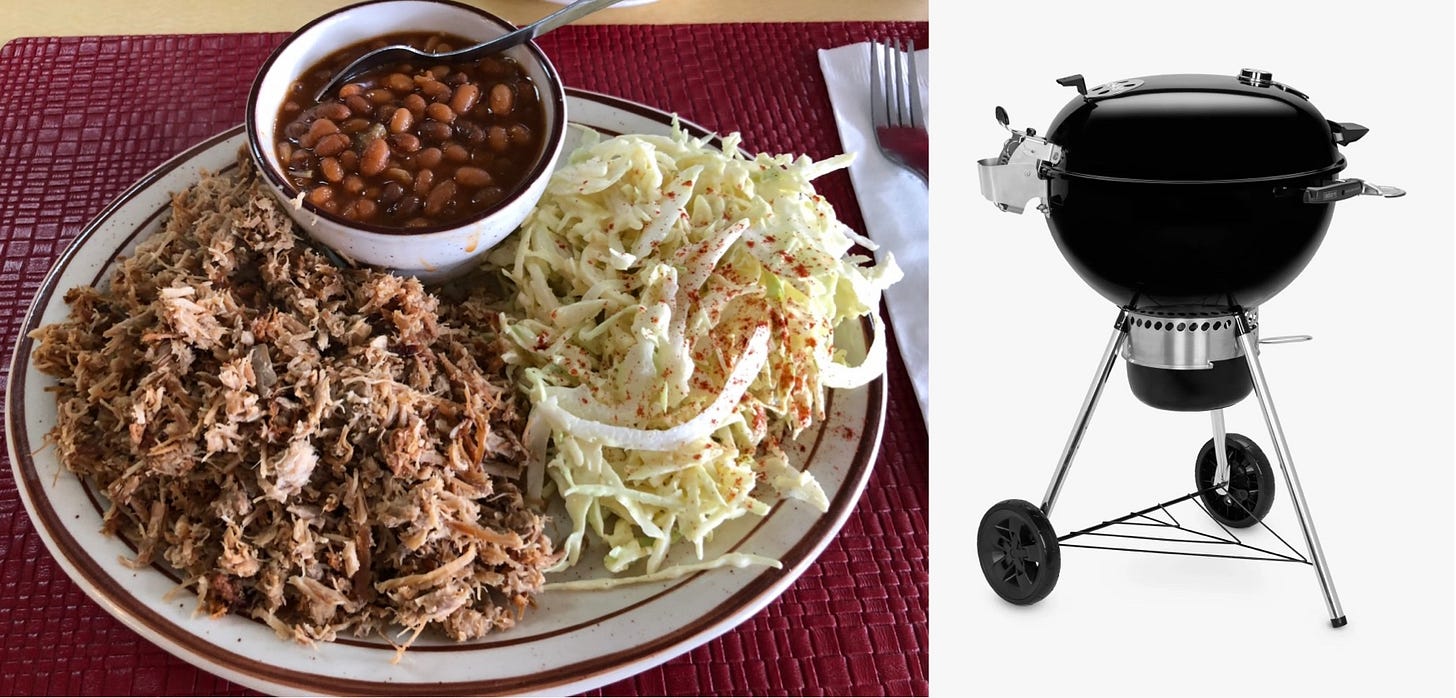

Barbecue is a style of food and can refer to one of several methods of preparation. It is not a cooking implement or piece of equipment. Ever. For clarity, I offer a visual guide. (Okay. So, there are strong feelings about this, with big differences in the U.S., and many people will disagree with me.)

Across the U.S., there are a number of overlapping regional styles of barbecue, but they share common origins: All are the result of efforts to take secondary cuts of meat and make them more pleasant (or even edible), usually through very slow cooking. They all have their roots in the history of European colonisation of North America. And they all emerged as a result of the work of enslaved men and women, either from Africa or of African descent, who built the traditions that we enjoy today, often by incorporating elements of African culinary heritage.

The choice of meat was usually driven by available land. In the 18th and 19th centuries, land in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina was mostly used for cash crops like tobacco, cotton, and rice. There was very little space for grazing, so cows were generally for milk and beef was uncommon — a delicacy for the particularly wealthy, just as they were in Europe. And it was too hot for lambs. So pork was the most common protein.

That story continued across the Deep South and the Gulf Coast. Economics dictated land be used for cash crops, cotton became dominant, and pork remained the meat of choice.

It wasn’t until exploration continued west of the Mississippi River and into the Great Plains that grazing large herds of cattle become economically sensible, and meat consumption gave way to beef.

So in Virgina and North Carolina, you find pork barbecue, usually from shoulder and often slow cooked over direct heat or braised rather than smoked. The sauce is vinegar based and sharp, sometimes with a little tomato or spicy pepper. In Virginia, there is also a tradition of chicken barbecue. The Crewe / Burkeville chicken festival remains a highlight of the culinary (and political) calendar.

In the Deep South, the focus is most commonly pork butt or pork ribs, more often smoked, and sauced with tomato, lemon juice, or chilli peppers.

More to the north in Memphis, Tennessee, you find the best expressions of pork ribs. Almost always smoked, flavoured either with a “dry” rub or served “wet” with a rich tomato sauce. A bit further north, in the Kentucky hills, you find mutton, done in a style similar to North Carolina pork barbecue.

Kansas City, Missouri is arguably the home of beef barbecue. The city’s position on the Missouri River meant that it was a key receiving point for cattle coming in from the range, to be butchered for export to big cities back east and abroad. And in 1908, it started to become big business. “Henry Perry, an African-American chef, first started slow cooking pork ribs over oak and hickory, drizzling them with a sauce consisting of molasses, chiles, and tomatoes. He served the meal in newspaper and sold it for 25 cents a piece, and the consumers' acceptance and love of barbecued meat went better than expected.”

In K.C., you’ll find big briskets, beef ribs, and burnt ends, often done with dry rub, while tomato-based sauces sweetened with molasses are offered as condiments. When you ask for a jar of barbecue sauce these days, it was probably inspired by Kansas City.

And then, of course, there’s Texas. Famous for its slow smoked briskets, there are actually a number of sub-regional varieties. But Texas beef is so good that it usually doesn’t need sauce, and is most commonly served without. Unsurprisingly, there are Mexican influences. You’ll find spice and big chilli heat.

(If you want more on American barbecue styles, Eater has a great overview.)

In recent years, these traditions have migrated around the U.S. and regional differences have eroded. Big chain restaurants have displaced smaller spots doing local styles. Barbecue is even popular in New York City. Like many kinds of food, it has become sadly homogenised. Pulled pork is basically a barbecue staple everywhere.

Here in London, there is small but growing number of places doing American barbecue. Texas Joe’s is the best and most authentic. But it’s run by a guy called Joe who is from Texas, so as long as he can get the right ingredients (which, he has told me, is not as easy as it sounds), it’s going to be good.

There are other pitmasters, like Snake Oil, who are carving their own path and doing great things.

Barbecue is fashionable. So much so that the Standard did a feature last week previewing the bets places for “London barbecue season.”

But before there was any of that, there was Bodean’s.

It was founded by Canadian restauranteur Andre Blais in 2002, rising eventually to as many as eight locations around town. But COVID and a drift of focus forced retrenchment, and five of those locations were eventually closed.

Earlier this year, a full reboot. With Blais now serving as a non-exec, in came a new MD and, shortly thereafter, a major free agent signing.

Richard Turner helped start Hawksmoor. He was behind PittCue, Blacklock, Turner & George, and the Meatopia barbecue festival. Restaurant Magazine calls him a “steak savant.” He’s got proper chef creds, too, having trained under Marco Pierre White, Pierre Koffmann, Joel Robuchon and Alain Ducasse. In April, he joined Bodean’s as Chef Director, and began rewriting the menu.

Gone are the rubbish burgers, hot dogs, and Tex Mex that Bodean’s embraced on its road to mediocrity.

In their place, a much simpler menu that focuses on Kansas City-style slow-smoked meats.

To prepare them, Bodean’s works from a central kitchen with six huge smokers, and delivers the finished articles to its locations each day. (That’s quite common in the U.S., where a local place might have a few locations.) And it means that Turner and his team can zealously guard quality.

So, is it any good?

In a word, yes.

The Carolina Pulled Pork is my go-to for quality calibration. In the past, Bodean’s was limp, reheated, and under flavoured.

Not any more. Turner has got the right level of heat in the smokers and a lot better attention to detail with the finishing in the restaurants. My portion would have fooled the most persnickety pitmasters back home. (Although the pickles were an unwelcome interloper.) And I was thrilled to see Smoked Turkey on the menu. This is a delicacy that more Londoners should get to know and love. I will definitely return in the future to try the brisket and burnt ends.

So, meat = good.

But we come now to the real secret of a top barbecue spot: Yes. The meat matters, but it’s the sides that separate outstanding from the merely great.

Turner’s new take on BBQ beans was fabulous. Strong with molasses and an array of spices, I’d have been happy eating them from a chuckwagon somewhere in Oklahoma. “Mac & Five Cheeses” would have been right at home in a Meat & 3 place in Nashville.

I do have a few quibbles. To be really authentic, Bodean’s needs a green side —either green beans or collard greens. Though I appreciate these might not sell, I’d like to see Turner give one of them a try. And this menu is screaming for cornbread. Most importantly, the selection of main “BBQ Dinners” doesn’t include a pork option. I built my own by ordering a side of pork, a side of beans, and a side of Mac & Cheese. Pork is a staple. Let it have its moment.

On the other hand, while I’m guessing that “Carolina Poutine” is probably a nod to the restaurant’s Canadian founder, cheese curds have no place on this menu. And sack the salads. No one is coming to a barbecue place to eat lettuce.

Quibbles aside, we come now to our central question: Is Bodean’s good for professional lunch (or dinner)? In its new form, the answer is a strong, “Yes.” It’s the perfect place for a team lunch or a casual group gathering with a few clients or contacts.

The new menu puts a big emphasis on its sharing platters — which are basically a ton of meats in various forms piled high with some topline sides and served for grazing. Roll up your sleeves before diving in. I assume wet wipes are available, though I forgot to check.

I’ve lived in London for 18 years, and throughout that period, Bodean’s has always been something of a disappointment.

I’m really pleased to say that, in its new form and with Turner’s guidance, it is very much reaching its potential and can go toe-to-toe with some of its more youthful competitors.

Quick hit: After a reboot and a new, simpler menu, it’s delivering solid Kansas City-style barbecue and excellent sides.

Details: Walk-in. 4 Locations. ££.

Restaurant website. More on Instagram.

Find it on Google Maps: Soho. Covent Garden. Tower Hill. Camden.

Thanks for reading this week’s review. Got any perspective on American barbecue? I’d love to hear it in the comments. And please do subscribe if you haven’t already.

Wow I remember Bodeans in Clapham High Street circa 2006. I remember it being mediocre as you say—a TGI Fridays in a different gown was my take at the time. I saw the title of your review land in my inbox and I thought, this can’t be the same place surely? Turns out it is and it isn’t. It just goes to show what a change in leadership can do to a place. Cheers!

I always have a soft spot for Bodeans on Poland Street. We visited for someone's birthday and some in our party were overly excited to see John Malkovich in an adjoining booth. The Tower Hill branch might be a better bet geographically these days, so might pop along for a fat-boy lunch.